In interpersonal interactions, we are often advised to learn to put ourselves in others’ shoes, in the pursuit of understanding and caring for others. However, this method of perspective-taking is actually imperfect. When we try hard to place ourselves in others’ positions, we may feel that we have a clear understanding of other people’s emotions, but this is still our own emotion, not the true feelings of the others. The concept of telepathy does not truly exist in reality.

In 1984, the internist Howard Beckman and his colleagues recorded 74 medical conversations that each began with the doctor asking the patient what their primary concern was. It was found that in discussing their concerns, 70% of the patients were interrupted within less than 20 seconds; and only 2% of the patients were able to fully express their thoughts and worries. While this study drew widespread attention in the medical field, 15 years later, Beckman found that doctors were still frequently and quickly interrupting patients.

For professionals, not everyone is born with the ability to listen attentively. Lacking this skill can add many challenges to their careers. Doctors who ignore listening and speak without thinking might miss crucial diagnostic information about their patients. Financial advisors, mentors, or managers who fail to spend a few minutes carefully listening to the needs of others might mislead clients, students, and teams, thereby wasting hours or even months of time.

So, why does it seem so natural that professionals often dominate conversations? One reason lies in our misunderstanding of the meaning of social skills. Over the past twenty years, I have conducted in-depth research on the issue of empathy. Empathy—defined by scientists as the ability to share, understand, and care about the experiences of others—is defined by non-scientists as “walking a mile in someone else’s shoes.” Psychologists call this method “perspective-taking” and have proven it to be a powerful tool; studies have shown that when people imagine themselves in the lives of others, they become more generous and reduce their prejudices against others.

Although perspective-taking helps us to become more caring towards others, it is still flawed in understanding empathy. Since we can never truly experience the feelings of others, so-called perspective-taking is actually filled with our own biases, and these biases are usually invisible to us. In 25 experiments, researchers Tal Eyal and Nick Epley had people imagine they were in someone else’s situation and found that perspective-taking made the participants more confident in their social insight, but in fact, their understanding of other people’s true feelings did not improve.

Eyal and Epley call this phenomenon “the perspective gap,” and it is ubiquitous. Experts are not aware of what non-experts do not understand, so they tend to use technical terms rather than simple everyday language.

In conflicts of interpersonal relationships, people often disagree on what they are actually disagreeing about, which further intensifies disagreements between the parties. At work, people in power struggle to understand the struggles of those without power. An executive considering the return-to-office policy might imagine how they would feel working in person. However, things are not always that simple.

Executives can afford to live closer to the headquarters, have access to high-quality childcare, and are well-respected among colleagues, and so they paint a rosy picture in their minds—one that most team members do not share. Empathy shifting considers empathy a personal exercise: it asks the empathic person only to understand what someone else is going through. But in reality, this is not true empathy, it’s mind-reading—which, of course, does not really exist.

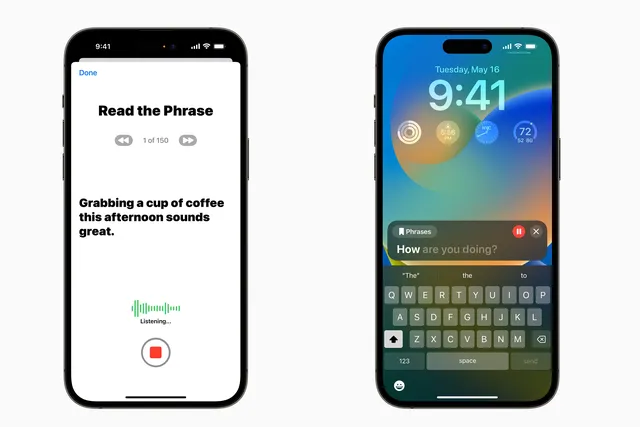

In fact, no one can generate empathy on their own. What great consultants, teachers, doctors, therapists, and friends do every day is to collaborate with others and reach mutual understanding through that collaboration. Scientists call this approach “perspective-taking,” which is about understanding others’ feelings by asking questions and listening actively. Perspective-taking is not as well-known as empathy shifting, but it is more precise and helps people understand each other more accurately.

Research has found that when people in power engage in “perspective-taking,” those without power feel heard, which can improve the relationship between them. When people stop to take perspective during disagreements, they can identify common ground and become more persuasive advocates for their own ideas.

For leaders and experts, it takes courage to admit that they do not understand others and to give them space to teach themselves. But fortunately, any of us can practice perspective-taking and get better at it over time. Here are some ways to start practicing perspective-taking:

Try using “looping” to deepen understanding. Looping is a simple perspective-taking technique commonly used by journalists, mediators, detectives, and other professionals who need to extract information from others. They start by posing a question, allowing the other person time to answer, not just ending the conversation after asking. Then they paraphrase what they heard and ask, “Did I get it right?”, or “What have I missed?” This process is repeated until both parties agree on the respondent’s experience.

Although simple, the method of looping is powerful. Those who employ looping develop an accurate understanding of someone else’s feelings, and it also impacts the respondent. Speakers feel truly listened to and are therefore willing to reveal more information. If the questioner encourages them to provide details, they might find new ways of describing their experiences, or even uncover hidden real thoughts or what they truly desire.

Circular method enhances the communication and connection between people. Many have experienced this: on the surface, we seem to be listening to others, but in reality, we are poised to express our own thoughts the moment it’s our turn to speak. This behavior of waiting for our turn to speak inadvertently reduces our true understanding of what the other party is saying.

Especially for those in leadership positions, who often believe they need to provide standard answers to all questions, they may not truly listen and understand the needs of others. This bias can not only mislead themselves but also potentially hurt others. Those with leadership or influence should reconsider their role—not always to provide the answers but to ask more constructive questions, or simply to focus all their attention on the current communication.

Listening may seem passive, but it actually requires deep thought. In an experiment where participants were divided into speakers and listeners, the results showed that when listeners were distracted, the content narrated by speakers became fragmented. If you are checking emails while “listening” to someone in a remote meeting, they can usually tell where your attention is.

The impact of “good” silence and “bad” silence in communication is starkly different, and both silently shape the relationships within teams and individuals. An ideal work environment should be filled with genuine listening, trust, and loyalty. The manifestation of leadership is sometimes not about speaking more, but about the right amount of silence.

Self-reflection after a conversation is a useful habit. Ask yourself: “What have I learned from this conversation? In what aspects was my previous understanding off, and now it has improved?” If you have only reaffirmed your previous views, you might have missed the opportunity to become a better listener.

Empathy is often seen as a performance—we try to show understanding of others, yet overlook the real clues that can help us connect. We should recognize that conversation is a co-creative process, and when we make room for each other to learn, it becomes more effective.